Sri Lanka’s War – two years on

MAY 19TH is the second anniversary of the Sri Lankan government’s announcement that its forces had killed Velupillai Prabhakaran, leader of the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. It marked the government’s definitive victory in a bloody 26-year civil war—one, moreover, that analysts, including this newspaper, had for years argued could never be won. Yet in the end victory was so complete that peace already seems permanent.

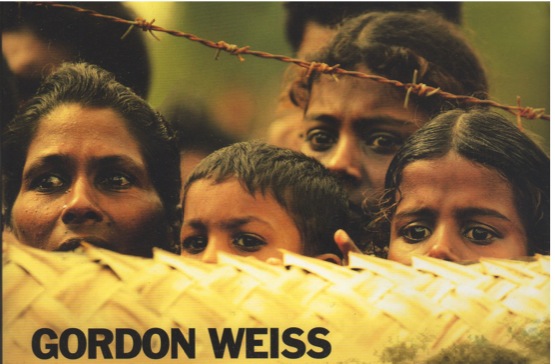

A book, published this week, by Gordon Weiss, the United Nations’ spokesman in Colombo in the final stages of the war, (“The Cage”*) is an excellent account of how that victory was won, and of the price paid for the present peace by Sri Lankans from the Sinhalese majority as well as the Tamil and Muslim minorities.

A book, published this week, by Gordon Weiss, the United Nations’ spokesman in Colombo in the final stages of the war, (“The Cage”*) is an excellent account of how that victory was won, and of the price paid for the present peace by Sri Lankans from the Sinhalese majority as well as the Tamil and Muslim minorities.

Despite all the horrors around the world since then, many will recall the sense of outraged helplessness felt internationally in the final months of the war. Their beleaguered forces, having in effect taken hundreds of thousands of civilians hostage in a dwindling patch of northern Sri Lanka (“the cage”), were pounded relentlessly. So were the civilians.

The book’s outline of Sri Lankan history suggests that this brutality was not an aberration for the country. Not only had the war with the Tigers always been savage. So had been the violence of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, or JVP, a group espousing a strange hybrid ideology of Marxism and Sinhalese chauvinism, which staged two bloody uprisings in 1971 and from 1987-1989, both suppressed with enormous loss of life.

The real value of “The Cage”, however, is its detailed account of the war’s denouement. It supplements and adds context to the findings of a report published in April by a panel of experts for the United Nations. Mr Weiss has done an excellent job of piecing together as accurate a picture as possible of what went on in the cage, which, at the time, the government sealed off almost entirely from outside observers.

In the process, he recounts, as do the UN’s experts, compelling evidence of inexcusable disregard for human life on both sides of the conflict. If some of the massacres and murders described do not constitute war crimes, it is hard to know what would.

Three factors helped the government get away with its ruthless approach. One was the sheer awfulness of the Tigers—as vicious and totalitarian a bunch of thugs as ever adopted terrorism as a national-liberation strategy. Whatever the government did, it could never be worse.

It seems to have come close however, helped by the second factor: tight information management and censorship, including the intimidation of the local press, and a willingness to tell bald lies to foreign leaders. Third, unlike, say, Libya, it had the backing of both India and a veto-wielding member of the United Nations Security Council, China. It is not an encouraging precedent for a new multipolar world order.

Sri Lanka’s government insists its forces pursued a policy of “zero civilian casualties”. It is now going on the propaganda offensive, organising an international counter-terrorism conference in Colombo at the end of this month, to advertise the success of its methods.

The government will doubtless rubbish this book, and point to it, like the experts’ report, as evidence of the UN’s prejudices against it. In fact the book, which also tells stories of individual Sri Lankan soldiers’ heroic efforts to save civilian lives, is scrupulously fair.

But it will make little difference to Mahinda Rajapaksa, Sri Lanka’s president, and his family, who, in the words of a Sri Lankan analyst quoted in the book, are “transforming Sri Lanka from a flawed democracy to a dynastic oligarchy”.

That description is true enough. But a troubling aspect which the book rather skates over is that the Rajapaksa clan seems, among the Sinhalese majority, to enjoy genuine popular support. And foreign criticism, such as the UN experts’ report and this book, only enhances its popularity.

That makes it still seem unlikely that there will be any true accountability for atrocities committed in Sri Lanka’s war. In that sense the book reads as a lament, not just for those slaughtered, but for what the author calls a “co-operative view of international relations”, which maintains that “the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians do count, and that the way you fight a war does matter, even when your cause is just.”

*The Cage: The Fight for Sri Lanka & the Last Days of the Tamil Tigers. By Gordon Weiss. Bodley Head; 384 pages; £14.99

Courtesy : http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2011/05/sri_lankas_war

October 7, 2011 at 8:23 pm

That addresses several of my concerns aactully.

August 16, 2011 at 1:57 am

[…] who has nominated extra-judicial killing as the Sri Lankan answer to special forces ops (read my book), and who has now provided his own special rationale as to why women do and don’t get raped in […]

June 15, 2011 at 11:25 am

I suppose a Professorial review by Rajiva (MP) will be forthcoming,

and two cents worth comments from Ivan and Dayan – when Payment is received from UK Bill Pottinger!!

Even the UN is not prepared to take into account its own Staff version

of happenings – so why the IC?