Why the United States Should Continue to Engage the UN Human Rights Council

A little more than a year after the United States took its seat for the first time as a member of the United Nations Human Rights Council, debates

persist over whether it should have continued the Bush administration’s policy of disengaging from the UN’s primary human rights body. This debate largely revolves around the issue of whether the council is a fundamentally flawed structure, and if so, whether the presence of the United States gives it undue legitimacy.

Is HRC flawed?

Freedom House’s own system of rating countries on political rights and civil liberties, with categories of Free, Partly Free, and Not Free, is often used to support the assertion that the council is fundamentally flawed. Critics point out how many countries in the Not Free category are able to win elections to seats on the council and then, not surprisingly, use their positions to shield themselves and their allies from criticism rather than to combat human rights abuses. Metaphors like “foxes guarding the hen house” are frequently invoked—and not altogether unfairly. A second pillar of the flawed-structure argument is the council’s continued disproportionate focus on Israel and the highly biased nature of the resolutions and decisions it has approved regarding that country.

These issues are by no means irrelevant, and this brief will explore each more fully. But the debates about the council must center on whether the body holds intrinsic value for the advancement of human rights despite its flaws, and whether strong engagement by the United States and other democracies that respect human rights increases that value. Freedom House believes the answer to both those questions is yes.

Elections and Membership

As a political body—a body comprised entirely of UN member states—the ability of the Human Rights Council to live up to its mandate to promote and protect human rights is only as strong as the commitment of its members. The composition of the council at any given time therefore plays an important role in determining how well or poorly it deals with pressing human rights issues. Nonetheless, there is not always a clear link between a

country’s domestic human rights record and its performance on the council. While the world’s most aggressive abusers of human rights—countries like China, Cuba, and Russia—invest tremendous resources in getting elected to sit on the council, and can be counted on to vote the wrong way on major resolutions and decisions in most instances, the reverse is not always true. In other words, countries with positive domestic records on human rights cannot necessarily be counted on to vote the right way on major resolutions and decisions. Countries in the middle—those with a Partly Free status according to Freedom House—likewise have mixed voting records that are as often swayed by pressure from leaders within regional groups as by human rights considerations.

Performance of Council in 2010-2011 by far the best

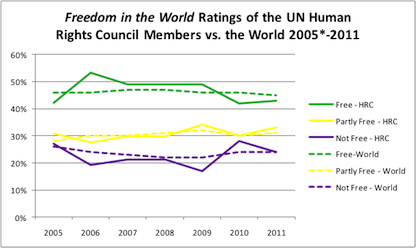

When it comes to resolutions that should be straightforward from a human rights perspective, such as those condemning human rights violations in North Korea or extending a mandate on Sudan, democracies like Ghana and Indonesia have voted against them, and others like India, South Africa, and South Korea have often abstained. Meanwhile, the composition of the council in terms of Free, Partly Free, and Not Free countries has been better than the world as a whole in every year since the council was established, until the 2010–2011 cycle, when it fared slightly worse (see chart). Yet the performance of the council in 2010–2011 was by far the best since it was established in 2006 in terms of taking strong actions on countries engaged in egregious abuses. In that year, which coincided with the first-time presence of the United States on the council, solid resolutions were adopted on Burma, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Syria. Entirely new mandates were created to promote freedom of assembly, prevent discrimination against women, and monitor violations of human rights in Iran.

Such results speak to the fact that the work of influential countries behind the scenes in Geneva and in national capitals to sway votes is of far greater importance than the simple breakdown of the council’s membership in terms of domestic human rights records. They also undermine the idea that an alternative body—a body that includes only democracies with strong human rights records—would necessarily perform better than the council, even if such an entity could be established.

Israel and Impunity for Authoritarians

There is no question that the UN Human Rights Council spends a disproportionate amount of time focused on human rights violations by Israel, and that the body uses overly harsh and biased language in the resolutions and decisions it adopts regarding Israel. Such resolutions hold Israel solely responsible for human rights abuses while withholding criticism of Palestinian groups in conflicts between the two sides. Israel remains the only

country in the world to be the subject of a permanent agenda item at the regular sessions of Fthe council, and it has been the subject of 6 out of the 17 special sessions held to date. (Other special sessions have focused on Sudan, Burma, Democratic Republic of Congo, Sri Lanka, Côte d’Ivoire, Libya, and Syria.)At the same time, a handful of countries with abysmal human rights records continually succeed in escaping scrutiny due to either their strong economic influence or their symbolic leadership in opposition to the Western or developed world. These countries—including notably China, Cuba, and Russia—are all but exempt from condemnatory resolutions and play a leading role in opposing other country-specific resolutions as a matter of principle, and in sponsoring initiatives that run counter to universal values.

It should be noted, however, that the biased treatment of Israel is not limited to countries with poor human rights records or even members of the Arab League or the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. The majority of Free and Partly Free countries on the council, including several from Western Europe and Latin America, have voted in favor of resolutions condemning Israel despite their biased nature. Likewise, all too many democracies in the developing world align their votes with China, Cuba, and Russia simply to counterbalance what they perceive as Western biases that favor political rights and civil liberties over economic, social, and cultural rights.

Why the Human Rights Council Is Relevant

Despite the presence and influence of countries with very poor human rights records, and despite its biased treatment of Israel, the council remains highly relevant both for its role in setting international norms on human rights and as the world’s only global human rights body. Precisely because countries that are seen as antagonistic toward the Western world and its values can run for and get elected to sit on the council, the body holds a degree of legitimacy that neither a regional organization nor a body established only by the world’s democracies could muster. Moreover, if one truly believes that human rights are universal and not merely the creation of the Western world or a luxury of developed nations, only a global body that is reflective of the world’s political landscape will have the credibility to create standards to which all populations can hold their governments accountable.

Although it has too often fallen short of the expectations of human rights organizations and experts, the council and its many tools—including special rapporteurs, independent experts, and the Universal Periodic Review process—have defended fundamental human rights and placed many of the world’s most egregious human rights abusers under a spotlight that otherwise would not exist. A country like Iran can easily dismiss resolutions by the European Union as products of Western bias or hypocrisy, but it has a much harder time explaining away resolutions passed by the Human Rights Council, a body on which members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation occupy over a third of the seats.

What Engagement Has Achieved

Since the Human Rights Council was created in 2006 to replace the Commission on Human Rights, Freedom House and a number of other human rights organizations have called for increased engagement at the council by the United States and other democracies to ensure that the battle over international norms is not tilted in favor of repressive states. The Obama administration responded not only by running for and winning a seat on the council in 2009, but by creating the first-ever U.S. ambassador-level position exclusively devoted to the council.

More importantly, the administration invested significant resources into winning key council votes on hotly contested issues surrounding freedom of expression and association, and with regard to country-specific situations. It did so through extensive outreach and negotiations with states in all five regional groups, both in Geneva and directly in the countries’ capitals. In other words, it invested the same kind of political capital that is effectively wielded by China, Russia, and Cuba—the kind of political capital that Americans should expect from a superpower founded on the principles of human rights.

In its first two years on the council, leadership from the United States helped renew country mandates on Somalia, Sudan, Burma, and North Korea; helped defeat persistent efforts by a number of Islamic countries to create an international blasphemy law; and was instrumental in creating a new and long overdue mandate dedicated to freedom of assembly, as well as the first country-specific mandate (on Iran) since the council’s creation. U.S. leadership also helped galvanize the council to respond quickly and appropriately to the repression of popular protest movements in Libya and Syria.

Recommendations

To further strengthen the legitimacy of the Human Rights Council and its ability to defend and promote human rights, the United States should:

(1) Maintain its seat on the council and continue to overcome regional or bloc voting by investing in cross-regional efforts to win key votes on fundamental freedoms and country-specific actions. This includes continued engagement with the strongest emerging democracies—Brazil, India, and South Africa—and urging them to set aside their traditional hesitancy to hold human rights abusers to account.

(2) Pressure other democracies, particularly in the developing world, to invest the resources necessary to run for seats on the council and to vote only for those countries that seek to uphold human rights at home and at the United Nations. Join those countries that have issued standing invitations to the special procedures mandate holders, demonstrating that the United States fully supports the council’s most effective mechanism and is open to investigations of its own human rights record.

(3) Engagement at the UN Human Rights Council requires significantly more than occupying a seat and voting according to human rights considerations rather than political ones. Progress is slow, and all battles worth fighting at this forum are fiercely contested by opponents of universal human rights. However, the benefits of engagement are many, and the costs of disengagement—in essence ceding the venue to the world’s autocracies—are far too high.

Paula Schriefer is Director of Advocacy at Freedom House.

A little more than a year after the United States took its seat for the first time as a member of the United Nations Human Rights Council, debates

persist over whether it should have continued the Bush administration’s policy of disengaging from the UN’s primary human rights body. This debate largely revolves around the issue of whether the council is a fundamentally flawed structure, and if so, whether the presence of the United States gives it undue legitimacy.

Is HRC flawed?

Freedom House’s own system of rating countries on political rights and civil liberties, with categories of Free, Partly Free, and Not Free, is often used to support the assertion that the council is fundamentally flawed. Critics point out how many countries in the Not Free category are able to win elections to seats on the council and then, not surprisingly, use their positions to shield themselves and their allies from criticism rather than to combat human rights abuses. Metaphors like “foxes guarding the hen house” are frequently invoked—and not altogether unfairly. A second pillar of the flawed-structure argument is the council’s continued disproportionate focus on Israel and the highly biased nature of the resolutions and decisions it has approved regarding that country.

These issues are by no means irrelevant, and this brief will explore each more fully. But the debates about the council must center on whether the body holds intrinsic value for the advancement of human rights despite its flaws, and whether strong engagement by the United States and other democracies that respect human rights increases that value. Freedom House believes the answer to both those questions is yes.

Elections and Membership

As a political body—a body comprised entirely of UN member states—the ability of the Human Rights Council to live up to its mandate to promote and protect human rights is only as strong as the commitment of its members. The composition of the council at any given time therefore plays an important role in determining how well or poorly it deals with pressing human rights issues. Nonetheless, there is not always a clear link between a

country’s domestic human rights record and its performance on the council. While the world’s most aggressive abusers of human rights—countries like China, Cuba, and Russia—invest tremendous resources in getting elected to sit on the council, and can be counted on to vote the wrong way on major resolutions and decisions in most instances, the reverse is not always true. In other words, countries with positive domestic records on human rights cannot necessarily be counted on to vote the right way on major resolutions and decisions. Countries in the middle—those with a Partly Free status according to Freedom House—likewise have mixed voting records that are as often swayed by pressure from leaders within regional groups as by human rights considerations.

Performance of Council in 2010-2011 by far the best

When it comes to resolutions that should be straightforward from a human rights perspective, such as those condemning human rights violations in North Korea or extending a mandate on Sudan, democracies like Ghana and Indonesia have voted against them, and others like India, South Africa, and South Korea have often abstained. Meanwhile, the composition of the council in terms of Free, Partly Free, and Not Free countries has been better than the world as a whole in every year since the council was established, until the 2010–2011 cycle, when it fared slightly worse (see chart). Yet the performance of the council in 2010–2011 was by far the best since it was established in 2006 in terms of taking strong actions on countries engaged in egregious abuses. In that year, which coincided with the first-time presence of the United States on the council, solid resolutions were adopted on Burma, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Syria. Entirely new mandates were created to promote freedom of assembly, prevent discrimination against women, and monitor violations of human rights in Iran.

Such results speak to the fact that the work of influential countries behind the scenes in Geneva and in national capitals to sway votes is of far greater importance than the simple breakdown of the council’s membership in terms of domestic human rights records. They also undermine the idea that an alternative body—a body that includes only democracies with strong human rights records—would necessarily perform better than the council, even if such an entity could be established.

Israel and Impunity for Authoritarians

There is no question that the UN Human Rights Council spends a disproportionate amount of time focused on human rights violations by Israel, and that the body uses overly harsh and biased language in the resolutions and decisions it adopts regarding Israel. Such resolutions hold Israel solely responsible for human rights abuses while withholding criticism of Palestinian groups in conflicts between the two sides. Israel remains the only

country in the world to be the subject of a permanent agenda item at the regular sessions of Fthe council, and it has been the subject of 6 out of the 17 special sessions held to date. (Other special sessions have focused on Sudan, Burma, Democratic Republic of Congo, Sri Lanka, Côte d’Ivoire, Libya, and Syria.)At the same time, a handful of countries with abysmal human rights records continually succeed in escaping scrutiny due to either their strong economic influence or their symbolic leadership in opposition to the Western or developed world. These countries—including notably China, Cuba, and Russia—are all but exempt from condemnatory resolutions and play a leading role in opposing other country-specific resolutions as a matter of principle, and in sponsoring initiatives that run counter to universal values.

It should be noted, however, that the biased treatment of Israel is not limited to countries with poor human rights records or even members of the Arab League or the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. The majority of Free and Partly Free countries on the council, including several from Western Europe and Latin America, have voted in favor of resolutions condemning Israel despite their biased nature. Likewise, all too many democracies in the developing world align their votes with China, Cuba, and Russia simply to counterbalance what they perceive as Western biases that favor political rights and civil liberties over economic, social, and cultural rights.

Why the Human Rights Council Is Relevant

Despite the presence and influence of countries with very poor human rights records, and despite its biased treatment of Israel, the council remains highly relevant both for its role in setting international norms on human rights and as the world’s only global human rights body. Precisely because countries that are seen as antagonistic toward the Western world and its values can run for and get elected to sit on the council, the body holds a degree of legitimacy that neither a regional organization nor a body established only by the world’s democracies could muster. Moreover, if one truly believes that human rights are universal and not merely the creation of the Western world or a luxury of developed nations, only a global body that is reflective of the world’s political landscape will have the credibility to create standards to which all populations can hold their governments accountable.

Although it has too often fallen short of the expectations of human rights organizations and experts, the council and its many tools—including special rapporteurs, independent experts, and the Universal Periodic Review process—have defended fundamental human rights and placed many of the world’s most egregious human rights abusers under a spotlight that otherwise would not exist. A country like Iran can easily dismiss resolutions by the European Union as products of Western bias or hypocrisy, but it has a much harder time explaining away resolutions passed by the Human Rights Council, a body on which members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation occupy over a third of the seats.

What Engagement Has Achieved

Since the Human Rights Council was created in 2006 to replace the Commission on Human Rights, Freedom House and a number of other human rights organizations have called for increased engagement at the council by the United States and other democracies to ensure that the battle over international norms is not tilted in favor of repressive states. The Obama administration responded not only by running for and winning a seat on the council in 2009, but by creating the first-ever U.S. ambassador-level position exclusively devoted to the council.

More importantly, the administration invested significant resources into winning key council votes on hotly contested issues surrounding freedom of expression and association, and with regard to country-specific situations. It did so through extensive outreach and negotiations with states in all five regional groups, both in Geneva and directly in the countries’ capitals. In other words, it invested the same kind of political capital that is effectively wielded by China, Russia, and Cuba—the kind of political capital that Americans should expect from a superpower founded on the principles of human rights.

In its first two years on the council, leadership from the United States helped renew country mandates on Somalia, Sudan, Burma, and North Korea; helped defeat persistent efforts by a number of Islamic countries to create an international blasphemy law; and was instrumental in creating a new and long overdue mandate dedicated to freedom of assembly, as well as the first country-specific mandate (on Iran) since the council’s creation. U.S. leadership also helped galvanize the council to respond quickly and appropriately to the repression of popular protest movements in Libya and Syria.

Recommendations

To further strengthen the legitimacy of the Human Rights Council and its ability to defend and promote human rights, the United States should:

(1) Maintain its seat on the council and continue to overcome regional or bloc voting by investing in cross-regional efforts to win key votes on fundamental freedoms and country-specific actions. This includes continued engagement with the strongest emerging democracies—Brazil, India, and South Africa—and urging them to set aside their traditional hesitancy to hold human rights abusers to account.

(2) Pressure other democracies, particularly in the developing world, to invest the resources necessary to run for seats on the council and to vote only for those countries that seek to uphold human rights at home and at the United Nations. Join those countries that have issued standing invitations to the special procedures mandate holders, demonstrating that the United States fully supports the council’s most effective mechanism and is open to investigations of its own human rights record.

(3) Engagement at the UN Human Rights Council requires significantly more than occupying a seat and voting according to human rights considerations rather than political ones. Progress is slow, and all battles worth fighting at this forum are fiercely contested by opponents of universal human rights. However, the benefits of engagement are many, and the costs of disengagement—in essence ceding the venue to the world’s autocracies—are far too high.

Paula Schriefer is Director of Advocacy at Freedom House.

February 21, 2012 at 7:47 pm

World powers, such as China and Russia, allied with the rest of the states opposed to The Administration

October 20, 2011 at 3:12 pm

[…] As part of its services, USAFIS informs its clients about issues relating to U.S. immigration. To become an U.S. citizen, an individual must have a Green Card and permanent residency for at least…U.S. citizens, Judge Scoles said "Many of you came to this country seeking freedom and opportunity. […]