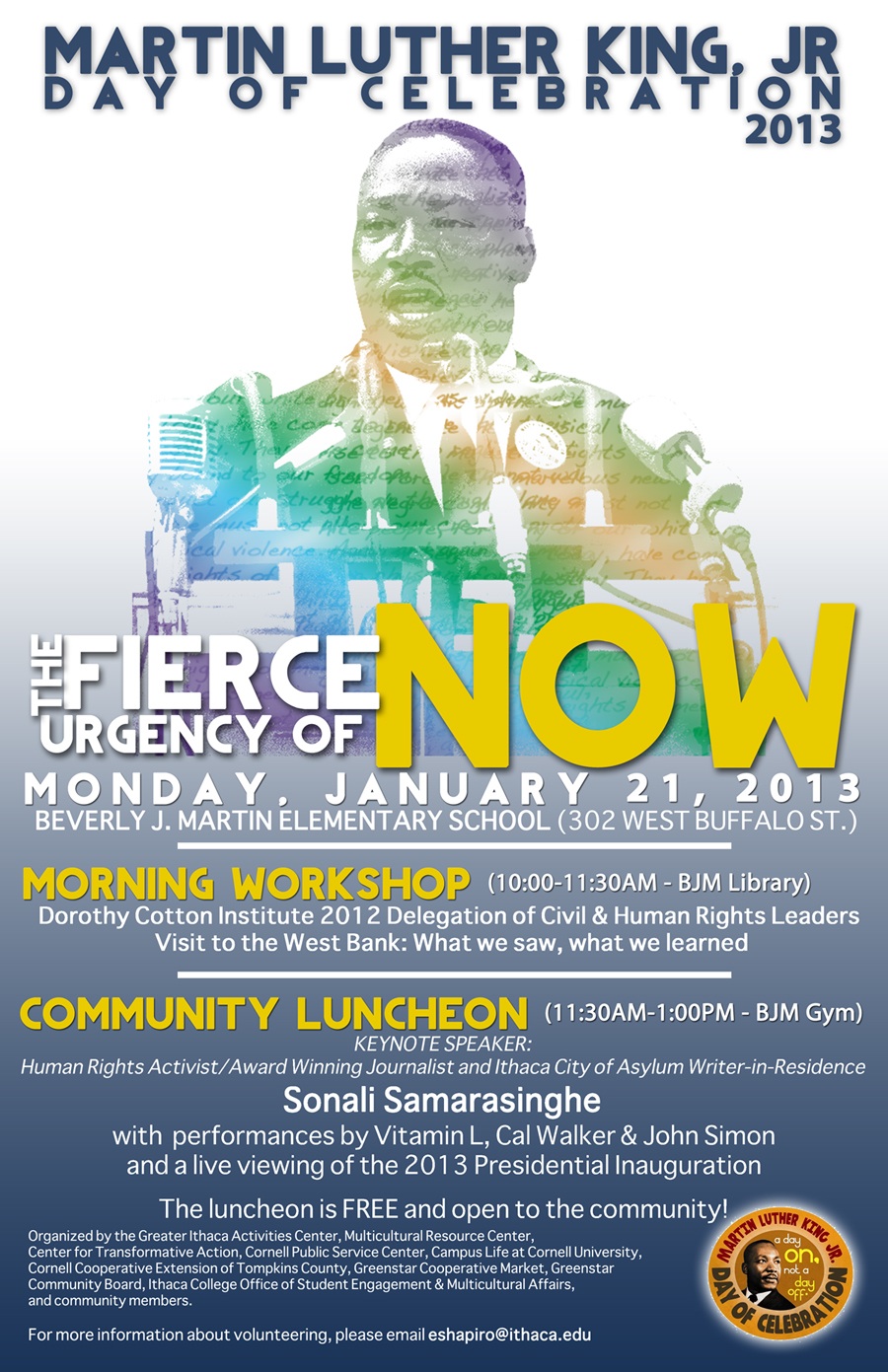

A shared dream: Sonali gives keynote speech on MLK Day on the ‘Fierce Urgency of Now’

21st January 2013

I am deeply honored to be apart of these celebrations in remembering one of the greatest spiritual leaders of all time – Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Thank you Don Austin for that generous introduction. Thank you also to the Greater Ithaca Activities Centre, to the Office of Student Engagement and Multicultural Affairs, The Centre for Transformative Action, and all the other organizers of this event.

It is significant that I a South Asian – Sri Lankan, stand here today with you to honor the life and work of Dr. Martin Luther King.

My presence here is a testament to the inspiration his life has been, not only to Americans, but to the entire world.

Four years ago today, in January 2009 I fled my country. That morning I had no time to pack suitcases. I was in hiding and running for my life.

I left my country with a small hand luggage. But I have a deep love of books. So in my home I had quite an extensive library. That morning as I packed my tiny bag in which I had hardly any room left, I went to my bookshelves and picked out four books. Four small volumes to take with me, as my only companions, on this journey into the unknown.

I knew that without these four books that I had grown up with: their pages saturated with my tears, my emotions, my fears, my doubts, my hopes:

I could not have stepped out as I did that day – leaving my friends, my family, my sources of comfort and love: to face a new world.

A few months after I fled Sri Lanka, I was in New York City and amidst that glorious feeling of relief and freedom and safety and the hope of new beginnings, I sat down to an early dinner at Ruby Foo’s Restaurant in Times Square.

With me I had a book. While waiting for my order I opened this book gingerly, for its pages were yellowed with age and my fingers trembled lest I handled it too harshly and the pages crumbled. On the inner page was my father’s bold scrawl of a signature.

As I started to read, a woman sitting at another table came up to me, her curiosity getting the better of her. She apologetically excused herself and asked me what it was that I was reading and why I was handling this book so carefully.

Is it some sort of ancient manuscript, is it from a museum she asked, pointing to the yellowed appearance and the frayed edges of the pages.

This book means a great deal to me I said. It belonged to my father. It is about a man my father taught us to revere, and it is about a life that has inspired me in my work and in my dreaming.

This book titled ‘What Manner of Man’ written by scholar and author Lerone Bennett Jr, was the biography of Dr Martin Luther King.

And it was one of the four books I brought with me as I fled my country.

Sri Lanka is where I come from. It is a resplendent island in South Asia endowed with natural beauty and resources beyond measure. From the 1500s Sri Lanka was invaded and colonized first by the Portuguese, then the Dutch and finally the British. We gained independence from the British in 1948.

Sri Lanka is a multi-ethnic, multi-religious country made up of a majority of about 72 percent Sinhalese 12 percent Tamils and 8 percent Muslims with about 2 percent Burghers and Malays. The Sinhalese are mostly Buddhist, the Tamils are mostly Hindu and there are about 8 percent Christians in the country.

I am a Sinhalese and thus I was heir to all the privileges of a majority community.

After Independence in 1948 the country was marred by race riots, communal violence and finally a brutal ethnic war as militant Tamil Groups fought for a separate state.

This war was fought for 27 years ending in May 2009. The last years of the war were particularly brutal. International agencies and journalists were denied access to the war zones as the government used scorched earth policies and indiscriminate aerial bombardment.

The Sri Lankan government was determined to wage a war-without-witness. A free press was not encouraged. Nineteen journalists have been killed in Sri Lanka since 1992.

It was in this backdrop that I was a journalist, editor and lawyer in Sri Lanka. My husband was the editor of one of the two newspapers I worked for, I was the Editor of the other. As journalists, we were critics of state sponsored violence and spoke up for human rights.

Week after week we exposed corruption in government and in military procurements. We spoke out against the colossal loss of innocent life, the vilification of journalists, activists and human rights defenders and the abduction or murder of anyone who dared to voice dissent.

For this, we were repeatedly threatened. Our newspaper offices had several times been burnt down over a period of years. But we got back up, swept away the ashes and continued to write and publish.

Over the years our newspapers had become a bastion for free speech, and for our audacity, we were now punished.

On the morning of January 8th 2009, my husband’s car was surrounded by 8 assassins on motorcycles, and he was bludgeoned to death. He was on his way to work. It was only by a bizarre twist of fate that I hadn’t been with him in the car that morning, having had to attend to a worker at home who had suddenly taken ill.

Two weeks after my husband’s assassination I fled Sri Lanka due to threats to my own life.

It was impossible to go on. The impunity with which the government was acting was unprecedented. There was no rule of law.

And I fled with this book.

So why this book? Tattered and falling apart as it is. Why not get a new copy from Amazon.com.

As I said we grew up in a country marred by violence, race riots and war.

One day when I was about fourteen years old race riots broke out. Compelled to stay indoors, due to an islandwide state imposed curfew, and told to stay away from the telephone by my parents, I grumbled to my father as teenagers sometimes do, that I was bored out of my wits and had a good mind to jump curfew and go to a friend’s house.

My father a man of discipline and a senior superintendent of Police, immediately went to his bookshelf filled with military books, law books, and books on counter terrorism and urban guerilla warfare and he picked out this one. The biography of Dr King.

Read it he told me, And then let’s talk about it.

Nine thousand miles away from the Lincoln Memorial, in Colombo, Sri Lanka I read

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character”

I was transfixed.

A year later my father introduced me to a wonderful movement called Initiatives of Change that based itself on the Gandhian concepts of nonviolence and absolute truth. A movement led in India by The Mahatma’s grandson, Rajmohan Gandhi.

Through the teaching of Gandhi and King and by their own example, my parents taught me early that above all, we have a responsibility, to right the wrongs we see before us.

As a senior police officer my father wielded considerable power. In the late seventies he was in charge of a large district in central Sri Lanka where Tamil/Sinhala ethnic riots had just broken out yet again.

We had received news that my father and his family too would be killed. My father first declared a district wide curfew, then he bundled my mum and his three youngest children including myself into the police car and he drove around his district not only to make sure that there would be no more incidents of violence but also to help those who were injured.

He visited every single home or business premises belonging to Tamils that had been attacked or burnt down by Sinhals mobs. While travelling we would come across the injured often beaten to within an inch of their lives. My father would stop, radio for assistance and stay with them till the ambulance arrived. He was strict and unrelenting with the rioters and compassionate with those who were victimized.

Because my father was on the streets himself supervising his men, it turned out that his district had one of the lowest casualty figures.

Yes, my father led by example.

As a police officer during a very violent time in our history my dad faced many challenges but he refused to compromise his principles or blindly follow orders if they were against his conscience. For this he suffered greatly in his work – often not given the promotions he deserved.

You may perhaps understand now, why this book, tattered and falling to pieces as it is, means so much to me and why it is imbued with so much power and significance.

The book’s author Lerone Bennett Jr and Dr King had been schoolmates and graduates of Morehouse College.

The book opens with this wonderful meeting in India between that great teacher of nonviolence revered in South Asia and around the world, Mahatma Gandhi, and a group of African American Pilgrims. The year: 1929.

At that meeting in 1929, Mahatma Gandhi sent a message to the black people of America.

“Let not the 12 million African Americans be ashamed of the fact that they are the grandchildren of slaves. There is no dishonor in being slaves. There IS dishonor in being slave owners. But let us not think of honor or dishonor in connection with the past. Let us realize that the future is with those who would be truthful, pure and loving. For as the old wise men have said, truth ever is, untruth never was. Love alone binds the truth and love accrues only to the truly humble.”

That message was published in July 1929 in America. After that, scores of African Americans would continue to make pilgrimages to Gandhi’s home in India.

Bennett describes another of these Pilgrimages in 1935, where the African American group discussed with Gandhi, oppression and Christianity. Gandhi asked them to sing him one of his favourite songs:

“Were You There When They crucified My Lord

Were you there When They Nailed Him to The Tree”

Bennett writes that Gandhi listened and sat silent for a moment. Then he said,

“Perhaps it will be through the African-American that the unadulterated message of non violence will be delivered to the world.”

Dr King was then six years old.

Years later Martin Luther King Jr. would fulfill Gandhi’s prophecy.

Gandhi’s method was to return good for evil, to work for ultimate reconciliation even with your worst opponent, and to openly break unjust laws and be willing to pay the penalty.

“Rivers of blood Gandhi said, may have to flow before we gain our freedom, but it must be our blood.”

Dr. King had come to see early that the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available in the struggle for freedom.

He was to later write that non-violent resistance was not a method for cowards.

Non violence was resistance to evil. It did not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding, he wrote.

It is based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice. There is deep faith in the future. And that is why the nonviolent resister can accept suffering without retaliation.

That is what Dr King taught us.

Surely, it was a method which my husband believed in too. When people asked my husband why he took such risks and warned him that it was only a matter of time before he would be killed, he would smile and say, “It comes with the territory, I know it is inevitable, but if we do not speak out now, there will be no one left to speak for those who cannot, whether they be ethnic minorities, the disadvantaged or the persecuted.”

My husband knew that one day he will have to pay the price – he always said he was ready for that. He did nothing to prevent that outcome: no security, no precautions. He wanted his murderers to know that he was not a coward, hiding behind human shields while condemning thousands of innocent people to death.

Yes, non-violence is not for the coward.

But even as we celebrate Dr King, there are still some 21 million people in forced labour or sexual exploitation around the world. About 3 people in every thousand are not yet free. These are only the documented. It is estimated there are millions who are not even a statistic.

There are 15.4 million refugees today

Last year 119 journalists were killed around the world

Every time some tragedy takes place the good among us stand up and say, No. Never again.

And yet, it happens over and over and over again with demonic repetition.

Since the Nuremburg trials in 1946 there have been an estimated 80 -100 million deaths due to war crimes or crimes against humanity.

For many, the dream is still to realize. For millions, freedom has yet to come. For thousands, help already came too late.

This is not a fight we can fight alone as south Asians, or journalists or Hindus or blacks or whites. It is a fight we must fight together as a global community. Because every time a little girl child goes to school in Pakistan, each time a child is freed from slavery in a shrimp farm in Bangladesh, each time a young black man feels he can walk safely home as an equal, each time a gay couple says I do, every time there is one less stare, one less insensitive remark, one less snub that makes the life of the minority, the other, the disenfranchised, a little less harsh, each time that happens, Dr King’s dream prevails.

Just another reason, that NOW is the time to act.

Thank you

Sonali Samarasinghe was the keynote speaker at the Martin Luther King Day celebrations in Ithaca, New York on January 21, 2013 at the Greater Ithaca Activities Center. Speaking to a packed house Samarasinghe received a standing ovation. Above is the full text of her speech.